Albumin in the Human Body: Structure, Functions, Clinical Testing, and Disease Associations

The Science of Albumin: From Structure to Clinical Significance

Albumin is the most abundant protein in human blood plasma. An average adult has about 35–50 g of albumin per liter of plasma, accounting for roughly half of all serum proteins. In practical terms, a one-liter sample of blood contains about 70 g of albumin, as illustrated by the beaker example often used in educational materials. Adult humans produce roughly 10–15 g of albumin per day in the liver, and the protein has a long half-life of approximately 19–21 days once in circulation. Albumin is synthesized exclusively by hepatocytes.

Historically, the presence of albumin has been noted since antiquity. Hippocrates in the 5th century BC described “foamy urine” in kidney disease, a phenomenon now understood as albuminuria. The protein was first crystallized from horse serum in 1894. In healthy individuals, serum albumin levels typically range from 3.5–5.0 g/dL (35–50 g/L).

Figure: 70 g of purified bovine serum albumin (white powder) in a beaker. This is approximately the amount of albumin protein present in one liter of human blood. Albumin is the main protein of plasma, carrying water and solutes through the circulation.

Molecular Structure of Albumin

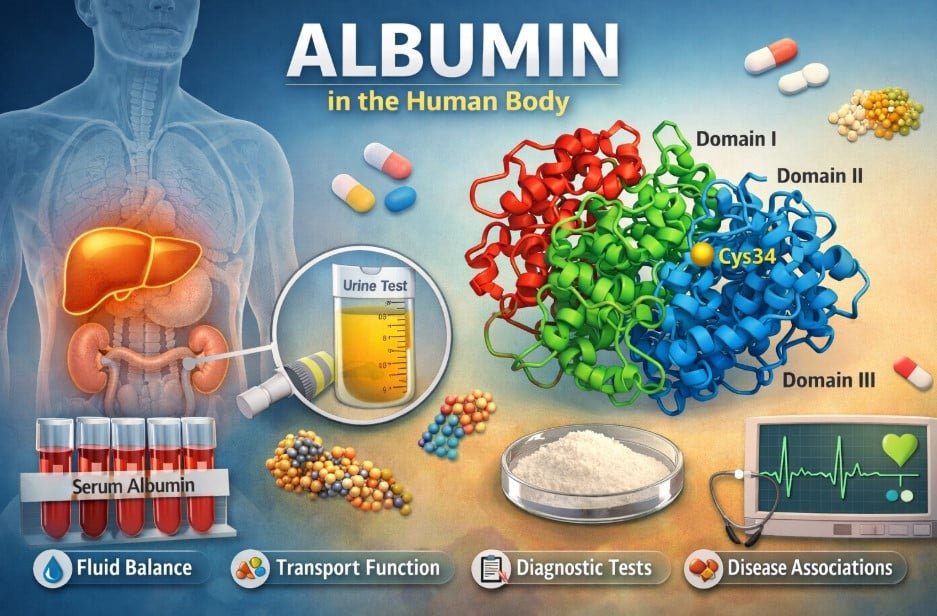

Human serum albumin (HSA) is a single polypeptide chain composed of 585 amino acids with a molecular weight of approximately 66.5 kDa. Its tertiary structure consists of three homologous domains (I, II, and III) arranged in a heart-like shape. Remarkably, albumin’s structure is composed almost entirely of alpha helices, with no beta-sheet segments, making it highly helical and structurally stable.

Each domain is connected by short peptide loops, resulting in a flexible and globular conformation. A defining chemical feature of albumin is the presence of 17 intramolecular disulfide bonds that link 34 of its 35 cysteine residues, leaving only one free cysteine (Cys34). This free thiol group is chemically reactive and plays a key role in albumin’s antioxidant activity.

Overall, human serum albumin is an acidic, water-soluble protein with an isoelectric point of approximately 5.1. It is not normally glycosylated, except for minor non-enzymatic glycation that can occur with aging or disease. The protein can withstand relatively high temperatures, up to around 60°C, without denaturing, reflecting the robustness of its helical structure.

Types of Albumins and Their Sources

The term “albumin” refers to a broad class of water-soluble globular proteins that coagulate when heated. In vertebrates, serum albumins circulate in the bloodstream, including human serum albumin and bovine serum albumin (BSA). All serum albumins belong to the albumin gene family, which also includes proteins such as alpha-fetoprotein and vitamin D–binding protein, and this family is found only in vertebrates.

Human serum albumin and bovine serum albumin share very similar amino acid sequences and biological functions, although BSA, commonly used in laboratory research, differs slightly in specific residues. Other vertebrates possess their own species-specific serum albumins, including birds, reptiles, and various mammals.

Beyond serum albumin, other albumin-type proteins occur in nature. Ovalbumin is the primary protein found in egg white and is produced by birds. Although it is unrelated to serum albumin in sequence, it is named for its solubility and functional properties. Ovalbumin makes up roughly 54% of chicken egg white protein and is a single-chain glycoprotein consisting of about 386 amino acids with a molecular weight of approximately 45 kDa. Unlike human serum albumin, ovalbumin is glycosylated.

Milk albumin, also known as alpha-lactalbumin, is another example. Alpha-lactalbumin is a small whey protein found in mammalian milk and plays an important role in lactose synthesis.

Plants also contain proteins referred to as albumins, particularly in seeds. In legumes and cereals, 2S albumins are a family of small, water-soluble seed storage proteins that provide amino acids for the developing plant during germination. Soybean and rapeseed seeds contain abundant 2S albumins that are rich in sulfur-containing amino acids. These plant albumins differ structurally from vertebrate serum albumin but share the common characteristic of being water-soluble.

Biological Functions of Albumin in the Human Body

Albumin plays multiple essential roles in human physiology. One of its primary functions is the maintenance of colloid oncotic pressure within blood vessels. Approximately 80% of plasma oncotic pressure is attributed to albumin. By retaining water within the vasculature, albumin prevents excessive fluid leakage into surrounding tissues and helps prevent edema. Its high concentration and molecular size make it the principal determinant of colloid osmotic balance.

Albumin also serves as a versatile carrier protein. It binds and transports a wide range of endogenous and exogenous substances. For example, human serum albumin binds at least 40% of circulating calcium, with the remainder carried by globulins. It transports free fatty acids, steroid hormones such as cortisol and testosterone, thyroid hormones, bilirubin, hemin, and numerous other ligands.

Many commonly used drugs, including warfarin, phenytoin, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, bind strongly to albumin. This binding significantly influences drug distribution, bioavailability, and half-life. Hydrophobic drugs often bind to specific regions on albumin known as Sudlow sites I and II. Through this reversible binding, albumin acts as a reservoir that buffers circulating concentrations of substances and reduces potential toxicity.

Albumin also exhibits enzymatic and redox-related functions. The free thiol group at Cys34 can scavenge reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, contributing to antioxidant defense in the bloodstream. Albumin can bind and neutralize pro-oxidant metals and compounds. It also contributes to acid–base balance, accounting for approximately 10–20% of plasma buffering capacity through its ability to bind protons and other ions.

Additionally, albumin has minor enzymatic or pseudo-enzymatic activities, such as esterase-like effects, and can influence nitric oxide signaling by binding S-nitrosothiols. Albumin also interacts with endothelial cells and helps regulate capillary permeability. Together, these diverse functions make albumin a highly adaptable and indispensable protein for transport and homeostasis.

Diagnostic Tests for Albumin

Blood (Serum) Albumin

Serum albumin is routinely measured as part of standard blood panels, including basic and comprehensive metabolic panels. The normal reference range in adults is approximately 3.5–5.0 g/dL. Values below this range indicate hypoalbuminemia and are clinically significant.

Low serum albumin levels are commonly observed in liver disease, kidney disease, malnutrition, chronic inflammation, infections, burns, and systemic illness. Clinicians interpret reduced albumin as a marker of underlying pathology rather than a standalone diagnosis. For example, chronic liver disease leads to reduced albumin synthesis, while kidney disorders can cause excessive albumin loss through urine. Severe dehydration can falsely elevate albumin levels due to hemoconcentration.

Urine Albumin

Albumin excretion in urine is assessed to evaluate kidney function. Standard urine dipstick tests detect only large amounts of protein, while more sensitive assays measure the albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR). A normal ACR is less than 30 mg of albumin per gram of creatinine. Values between 30 and 300 mg/g indicate microalbuminuria, which is an early marker of kidney damage, particularly in diabetes and hypertension. Values above 300 mg/g indicate overt proteinuria.

Persistent albuminuria is a strong indicator of renal pathology. Clinicians often use urine albumin testing to screen and monitor patients at risk for chronic kidney disease.

Interpretation and Relevance

Abnormal albumin levels in blood or urine provide important diagnostic information. Low serum albumin often prompts further evaluation for liver dysfunction, kidney disease, malnutrition, or systemic inflammation. Similarly, the degree of albuminuria helps stage kidney disease and assess progression. Although albumin levels are influenced by multiple factors, they remain valuable clinical indicators when interpreted in context.

Disease Associations of Abnormal Albumin Levels

Hypoalbuminemia

A serum albumin level below 3.5 g/dL is common in many disease states. In liver cirrhosis and severe hepatitis, impaired hepatocyte function leads to reduced albumin synthesis. In nephrotic syndrome, including conditions such as diabetic nephropathy and membranous nephropathy, large quantities of albumin are lost in the urine, resulting in markedly low serum levels.

Severe malnutrition, particularly protein deficiency as seen in conditions like kwashiorkor, reduces the substrates needed for albumin synthesis. Systemic inflammation and acute illnesses such as sepsis, burns, and cancer cachexia suppress albumin production and increase vascular permeability, further lowering circulating levels.

The clinical consequences of hypoalbuminemia include edema, ascites, and pleural effusions due to reduced plasma oncotic pressure. Low albumin is also considered a marker of disease severity and poor prognosis. Hospitalized patients with persistently low albumin levels experience higher rates of complications and mortality.

Hyperalbuminemia

Elevated serum albumin levels are rare and usually reflect dehydration rather than true overproduction. In clinical practice, high albumin levels prompt assessment of a patient’s fluid status rather than concern for albumin excess.

Albuminuria

Under normal conditions, the kidneys retain nearly all circulating albumin, allowing only minimal leakage. Persistent albuminuria indicates glomerular damage. Microalbuminuria serves as an early warning sign of diabetic or hypertensive kidney disease. In nephrotic syndrome, albumin loss can exceed 3.5 g per day, accounting for the majority of urinary protein loss. These patients often develop edema and hyperlipidemia, making albuminuria a key diagnostic feature of renal disease.

Albumin in Clinical Treatments

Albumin’s colloid properties have led to its therapeutic use in fluid management and critical care. Human serum albumin solutions, derived from pooled donor plasma, are available in different concentrations. A 5% albumin solution is approximately iso-oncotic with plasma, while a 25% solution is hyperoncotic. Administration of concentrated albumin can significantly expand intravascular volume relative to the volume infused.

Volume Resuscitation

Albumin has historically been used for volume expansion in shock and hypovolemia. However, large clinical trials have shown no overall survival benefit of albumin compared with crystalloid solutions such as saline. In some patient groups, including burn patients, albumin use has been associated with worse outcomes. As a result, current guidelines do not recommend routine albumin use for general fluid resuscitation, particularly given its high cost.

Cirrhosis and Paracentesis

Albumin plays a well-established role in the management of advanced liver disease. Following large-volume paracentesis for ascites, albumin infusion reduces the risk of circulatory dysfunction and hepatorenal syndrome. Albumin administration in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis has been shown to lower rates of renal failure and mortality. For these indications, albumin remains a standard and evidence-supported therapy.

Other Uses

Albumin is commonly used as a replacement fluid in therapeutic plasma exchange and during cardiopulmonary bypass or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation to maintain oncotic pressure. Experimental approaches, such as albumin dialysis systems for liver failure, use albumin’s binding capacity to remove toxins. Although albumin infusions are sometimes used to correct hypoalbuminemia, treating the underlying cause remains the primary goal.

Overall, albumin therapy is beneficial in specific clinical scenarios but offers limited advantages as a routine resuscitation fluid. Clinicians must balance its physiological benefits against cost and evidence-based outcomes.

Conclusion

Albumin is an exceptionally important biomolecule in human health. It functions as a multifunctional plasma protein that maintains vascular volume, transports nutrients and drugs, buffers blood pH, and protects against oxidative stress. Abnormal albumin levels signal significant underlying disease, making albumin measurement a routine and valuable clinical tool.

Although albumin infusions are now used more selectively, the protein’s physiological importance remains unquestioned. Ongoing research continues to explore innovative applications of albumin, including its use as a drug carrier and therapeutic platform. A clear understanding of albumin’s structure, functions, and clinical relevance is essential for healthcare professionals and beneficial for the general public. Once a historical observation noted by ancient physicians, albumin remains central to modern physiology and medicine.

Read More Blogs: Speciering and Biodiversity: Inside Nature’s Method of Species Formation